“The most active spirit in the dissenting group”: Universalism, Democracy, and Antislavery in the Hartford of John Milton Niles, 1816-1856. Journal of Unitarian Universalist History, pg. 100-126 (Summer 2015), Robert Reutenauer

The Reverend Daniel Foster was forthright in his encouragement of the freethinking members of the Poquonock Congregational Church in their apparent attraction to Universalism. His liberality soon went too far, however, for the Windsor, Connecticut church elders; in 1783, they asked him to leave its “troubled” pulpit. It was distressing to these Yankees that the Calvinist orthodoxy of human depravity, limited atonement, and the futility of individual action was giving way to the optimism of moral free agency and the simple creed of salvation for all under the care of an eternally benevolent deity.

Soon after the election of Thomas Jefferson to the presidency in 1801, the Poquonock Universalists, by then a majority among the faithful, gained control of the church society, the building, and its funds. Windsor, home of the Poquonock congregation, was one of only a handful of towns in Connecticut to send Jeffersonians to the legislature during the democratic “Revolution of 1800.” Only fifteen or so of these “Jacobins,” in the language of the dominant Federalist Party, held office in the General Assembly in 1799. By 1803, about forty of the two hundred members in the lower house were Jeffersonian Republicans. The near simultaneous emergence of these two developments – liberal religion and “democracy” – was no accident; and in the early life of John Milton Niles, they would together collide with the Connecticut Standing Order.

As a young boy growing up in Windsor, on a farm just south of the fractious Poquonock church, John Milton Niles was an early witness to the on-coming democratic assault on the status of Federalist political, religious, and economic elites. Of five children born to Moses and Naomi Niles, John was the second son, born in August 1787. After Moses died, Niles took responsibility for the farm and his younger siblings, while also attending the local common school and worshipping with the Universalists. By his late teens, he was teaching at the school, work he left in his mid-twenties to study law in the office of a local Democratic- Republican.

After the War of 1812, Niles ventured beyond rural Windsor into the often-hostile Congregationalist and Federalist stronghold of Connecticut. About this time Episcopalians were finally ready to end their erstwhile junior-partner status in the Standing Order. They had become frustrated with the General Assembly’s continued unwillingness to charter an Episcopal college. A scandal in which funds from the Episcopal-chartered Phoenix Bank were reportedly diverted to Yale College was the last straw. Episcopalians joined Methodists, Baptists, and freethinking dissenters like Niles to inaugurate the American Toleration and Reform Party in 1816. Extension of the suffrage to all free white males, religious toleration, judicial reform, separation of powers, disestablishment of the tax-supported Congregationalist Church, and a written constitution to replace the still-operative royal charter of 1662 were the policy goals of this movement.

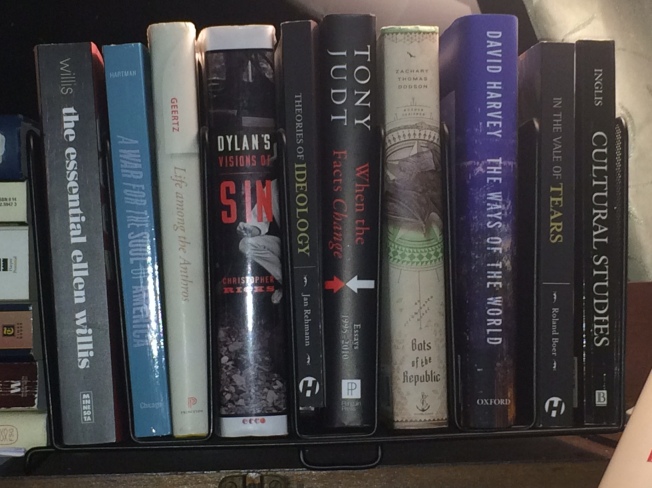

In support of the cause, Niles issued a reprint of the first American edition of The Independent Whig, a series of anticlerical essays known as Cato’s Letters, authored in 1716 by the British “commonwealth men,” John Trenchard and Richard Gordon. The first American edition appeared in 1724 and was extremely popular and influential among the early revolutionary generation. In his lengthy preface, Niles reminded his readers that the original publication of these essays in London had “brought on the most violent opposition and attacks from the bigots and the legal hierarchy.” To publish them again, here and now, was worth the risk, he contended. Only by “free enquiry” and the “circulation of ideas” can civil liberties exist.

He targeted the clergy, “who in despotic governments …will always be found in league with the oppressor,” calling them the main obstacle to free thought in Connecticut. He accused them of approaching their ministry as “a trade and religion itself as merchandise.” The Congregationalist monopoly on this “trade” in Connecticut was enforced by the state government. He complained of the clergy’s “peevishness of temper, and the extreme impatience with which they hear contradiction. A furious and implacable spirit of persecution,” awaits those who cross them.

The church-state establishment was, according to Niles, the primary impediment to the progressive improvement of society. Both institutions, civil and religious, were corrupt, “leading to superstition and intolerance in the one and oppression in the other.” The remedy, Niles concluded, was “democracy”— popular self-government, within a new constitutional framework. Sustaining this critique would be central to the life and work of John Niles for the next forty years.

anger leads these efforts, and has done a wonderful job making sure that we

anger leads these efforts, and has done a wonderful job making sure that we itutional guarantees (13th, 14th, 15th)

itutional guarantees (13th, 14th, 15th)